I was nearly in a tornado this weekend.

In what is surely one of the universe’s great ironies while visiting Springfield, Illinois to research the Tri-State Tornado of 1925, there was another tornado. At last count, there were five tornadoes in Illinois this weekend and seventeen confirmed tornadoes in Indiana.

We could see a storm moving into town from our hotel room. It came blowing through with sheets of torrential rain. Then the sirens went off and everyone fled to the basement. Amid a few upset kids and guests unsure how to get their WiFi to work, I was thinking, “This is precisely the same weather that happened March 18, 1925.”

As I’ve been researching the events that led up to what was then called “The Great American Tornado”, I’ve struggled to answer a few questions:

- How is it possible some people describe a day as “chilly and cool” and others “kind of muggy” in precisely the same time and place?

- How is it possible this storm didn’t make a sound, wasn’t visible, and almost no one saw it coming?

- Why do all the existing books on the Tri-State Tornado seemingly forget about some of the rural areas?

- Why is every library in Springfield called “The Lincoln Library”? Shouldn’t there be only one true Lincoln Library?

I got all my answers this weekend to everything but #4. That one remains a mystery.

It’s easy to forget in the doldrums of winter, but temperatures can change fast in March and April. And the dividing line between “It’s cool and I need a jacket” and “It’s warm and I need to wear lighter clothing” is only about 10-15 degrees. At fifty degrees most people would reach for a jacket, especially if it’s raining or windy. At sixty or sixty-five degrees most Midwesterners are ready to doff the flannel and don cotton tees and tanks.

On March 18, 1925, most people remember the day starting off drizzly and wet, but most kids remembered not having to wear jackets at recess. This, I’ve also learned, can be explained by the higher levels of brown fat kids carry compared to adults. All these things can be true at roughly the same time.

It’s also evident after literally watching this storm this weekend that a cloudy afternoon with rain in the distance forms a sort of invisible wall. Most people in 1925 described it as a sort of “rolling fog”. Some described it in a variety of colors, but most of the time people referred to it as “thick”, “black”, “brown”, or a “boiling fog”. Some even thought it was a dust storm. Watching this storm this weekend roll in from a distance it’s clear that’s a reasonable experience.

Not every storm makes a tell-tale “whistling” or “freight train” sound, either. The sound of wind and rain on top of you often drowns out even a monster tornado a few miles away. It was incredibly windy on March 18, 1925, just as it was across much of the Midwest this weekend.

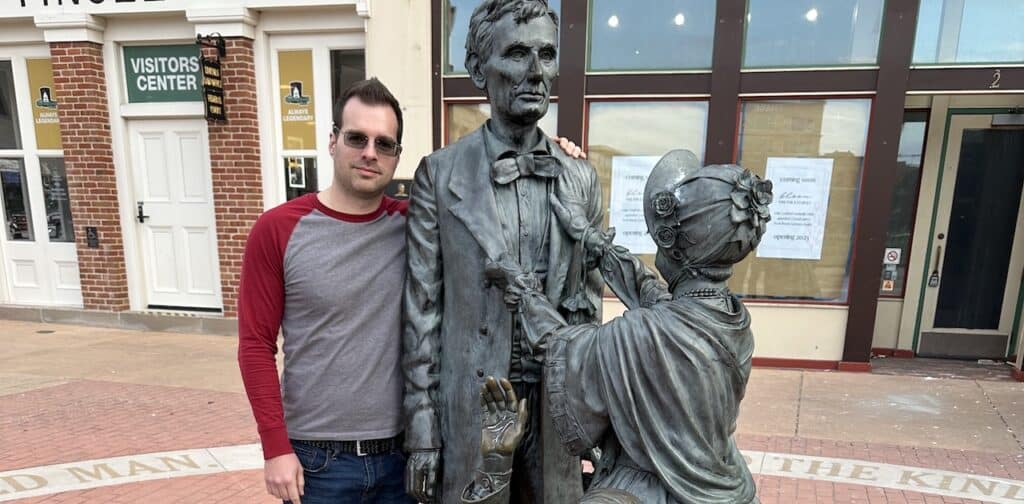

As I visited the Lincoln Presidential Library after visiting the Lincoln Public Library and, uh, the Lincoln…Library (seriously, there are three. I get it, Lincoln was your native son, but come on), I sat for hours scrolling through newspaper microfilms. I have to hand it to researchers who don’t know what dates they’re looking for. My research is well-defined geographically with a timeline that is universal, so if I can at least find a microfilm or newspaper, I’ve got a solid hunch where to look.

Speaking with a researcher at the Illinois State Library (which is now known as, you guessed it, “The Lincoln Library”), he told me the Lincoln Presidential Library was charged with preserving every newspaper in Illinois. Thumbing through miles of microfilm, I thought, “No one else has probably looked these up before.” That was kind of exciting.

There are other books on the Tri-State Tornado of 1925. Peter Felknor’s is probably among the best, as it’s a word-for-word oral history project among survivors who were children at the time. He’s probably the last person to make an effort among that generation before they died.

I, however, am probably the first person with the advantage of technology, search engines, optical character recognition, and online databases. This, however, was an advantage I was glad to start with but have been cautious not to rely on.

For one thing, many digitized papers and records are done primarily how you think: based on city size, perceived importance, and access to such systems. Smaller newspapers, like those in White County, Illinois or Pike County, Indiana, are largely gone. The papers have folded, been merged or bought out, or just vanished with time. Since there’s no existing newspaper with an interest in selling those to online databases, they’re kinda just shoved in drawers. Accessing what’s left of them requires physical trips to local historical societies or state libraries. That takes time, money, and patience. (Now’s probably a good time to say you can become a Supporter and a few bucks a month can help defray those costs.)

It’s also an unfortunate continuation of an age-old trend: larger population centers get more attention, even when the suffering in smaller, rural communities is proportionally worse or insufferably longer. Gorham, Illinois, for instance was 100% destroyed along with Annapolis, Missouri and Griffin, Indiana. Those residents’ lives were so cleanly swept away they didn’t even have neighbors across town to turn to for shelter. They slept in overturned train cars and tents for days. And because they had comparatively fewer people, fewer people were available to carry a cry for help. As ambulances and fire companies raced for Murphysboro, Illinois, people in West Frankfort, Illinois were still walking around in a daze, unable to access more than a single doctor at best.

So I’m glad I got the chance to visit one of the seemingly hundreds of Lincoln Libraries in Springfield. I discovered dozens of old newspaper clippings, photos, and stories from areas that time has nearly forgotten. They’ll make for a better book.