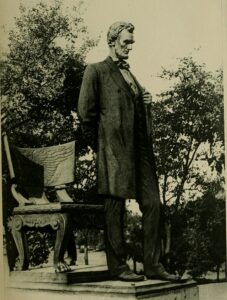

You’ve probably never heard of the sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens, but you’ve probably seen his work. Born in 1848, much of his career in the late nineteenth century included works of Diana, on display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, and Abraham Lincoln. The statue of Lincoln in Chicago was even used as the reference for Lincoln’s head on a postage stamp.

I’m fascinated how Saint-Gaudens became so good.

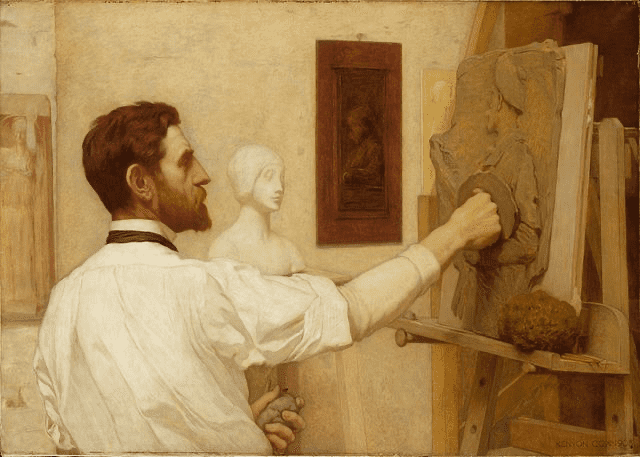

The gist: he was born in Ireland and the family immigrated to New York when he was six months old. For all intent, he was American. Fascinated by painting and art, he studied in New York as an apprentice under two professionals and then enrolled at the National Academy of Design. Thing was, the United States didn’t really have a great art scene in the 1860s. To be truly excellent in art you had to travel to Paris.

Saint-Gaudens traveled to Paris in 1867 and studied under two more masters before traveling to Rome to study architecture. Later in life, he returned to the United States, but in between he did commissions and works for Kings, royalty, Presidents, and significant pieces of art that are still with us today.

(As an aside, this was top of mind after listening to a clip of Gordon Ramsay talking about his experience becoming a chef. First, he was told to get to London, so he did, and studied there for a few years before realizing the best chefs were in Paris. So, to Paris he went despite not speaking French, until later returning to London.)

Augustus Saint-Gaudens did what few people do today: he figured out who was the best at something and went to those places and people. This despite travel and learning being significantly more accessible to the average American today.

In the period of about 1870-1900, hundreds of Americans made the journey to Paris and we were all better for it. They learned new skills that came back to America in the form of cuisine, sculpting, paintings, portraiture, writing, and craftsmanship.

Importantly, Saint-Gaudens took his time. He would rework pieces—often at a significant personal expense—because they weren’t good enough. When asked why he was so focused and particular about his work he replied, “Because sculptors know their work is permanent.”

This, too, has been top of mind as I continue to wrestle with the fleeting nature of the Internet and online work. The Internet promised to be this great depository of information that “never forgets”. Yet so much today is temporary. People flush away otherwise robust websites, drafts, products, and so on and replace them simply because they get bored of looking at them. Iteration is considered boring, even if incremental improvement over a period of two years can produce more dramatic results in just about everything compared to a flurry of up-front activity.

It’s unrealistic that everyone could always travel around the world to study from the best people in a field. But here, too, the Internet promised us accessible learning, but almost no one thinks the pandemic-induced e-learning so many of us have been thrust in is great. Online learning seems to be better than no learning but is clearly not a path to mastery in much of anything. And almost no one wants to admit their nearest City is anything less than capable of producing world-class anything.

Mastery comes from the deliberate practice of slow, methodical, discomfort and care. Augustus Saint-Gaudens evidently understood that and spent a month on a rickety wooden ship to cross the Atlantic at great risk to his life just to pursue it. His talent shined as a result.

I wish I could figure out how to do that. Somehow I don’t think a MasterClass subscription is going to cut it.

I liked the Augustus story.