“10 O’Clock Line” Treaty has a significant role in Hoosier history

A curious historical marker sits along US 40 about half an hour’s drive east of Terre Haute. The marker reads: “10 O’Clock Treaty Line. Runs northwest-southeast through this point. On September 30, 1809, Indiana Territorial Governor William Henry Harrison obtained for the United States almost three million acres from the Potawatomi, Delaware, and Miami tribes.”

The simple marker was erected in 1966 highlighting 150 years of Indiana statehood. Drivers passing by today probably pay little attention to it or don’t know about the long-forgotten land acquisition event that happened nearby. The sign also carries the heavy burden of ignoring what the 10 O’Clock Treaty Line meant for early Hoosier settlers and the multiple Native American tribes already living in the Indiana territory.

The Treaty — formally called “The Treaty of Fort Wayne” — purchased a tract of land encompassing some or all of present-day Vigo, Clay, Owen, Monroe, Jackson, Lawrence, Greene, Sullivan, Daviess, and Martin counties. A supplemental treaty would later bring in most of Randolph, Wayne, Fayetteville, Union, and Franklin counties.

When Indiana was admitted to the US as a state in 1816, the 10 O’Clock line marked the organized, functional northern boundaries of the early state. The line also marked settlement limits for Brownstown, Spencer, Bloomington, and other small towns along its shadow.

Indiana among first US territory to ban slavery and promise education

The idea that the country should grow westward was apparent to many Americans from the beginning of the revolution, even before the United States of America was a country. The Congress of the Confederation—a precursor to the US Congress—had already established the Northwest Territory in 1787 while the young nation was still recovering from the Revolutionary War. The US Constitution wouldn’t be fully ratified until a year later in September of 1788. Yet growth was unavoidable, and the Northwest Ordinance established the first land area after the original thirteen colonies.

The new territory represented the next frontier, with a land area larger than all of France, and included present-day Ohio, Michigan, Indiana, Illinois, Wisconsin, and a portion of Minnesota. Early American settlers streamed into the wild, untamed, and densely forested area in pursuit of new land and resources.

Governed only by martial law until the number of free white men exceeded 5,000, the new western frontier also represented the country’s most progressive ideals. The territory was the first to ban slavery, promote freedom of religion, and promise free and public education for everyone. The first university in the new region established itself in 1801 as Jefferson Academy. It would later rename itself to Vincennes University, which remains the oldest university in the territory.

A few brave settlers and warriors already existed in the northwest. The British had outposts spawning southward from Quebec. Clarksville, Indiana, was among the few French colonies. The Delaware, Miami, Potawatomi, Shawnee, and dozens of other smaller Indian tribes called the territory home, too.

As white settlers traveled westward, conflicts between settlers and Native Americans inevitably led to wars and a series of treaties, almost all of which would be favorable to settlers while pushing tribes further westward as promises were broken.

Once the population grew past 5,000 white men, a modest but formal government was established in present-day Marietta, Ohio to help maintain order. It would cease to exist after Ohio became a state on March 1, 1803. A few months later, on July 4, 1800, the remaining Northwest Territory, minus Ohio, would bear the name “Indiana Territory”.

The new Indiana territorial governor, William Henry Harrison, set out from Vincennes to the military outpost of Fort Wayne with the blessing of President James Madison nine years later in 1809. Madison charged him with negotiating a treaty with the many tribes in the Indiana territory and purchasing additional lands favorable for the United States. Accompanied by his secretary, Peter Jones, along with an interpreter, a servant, and two Indians, the party traveled along one of the few new roads which cut northwest across the region.

Nearly 900 arrive at Fort Wayne for negotiations with Harrison

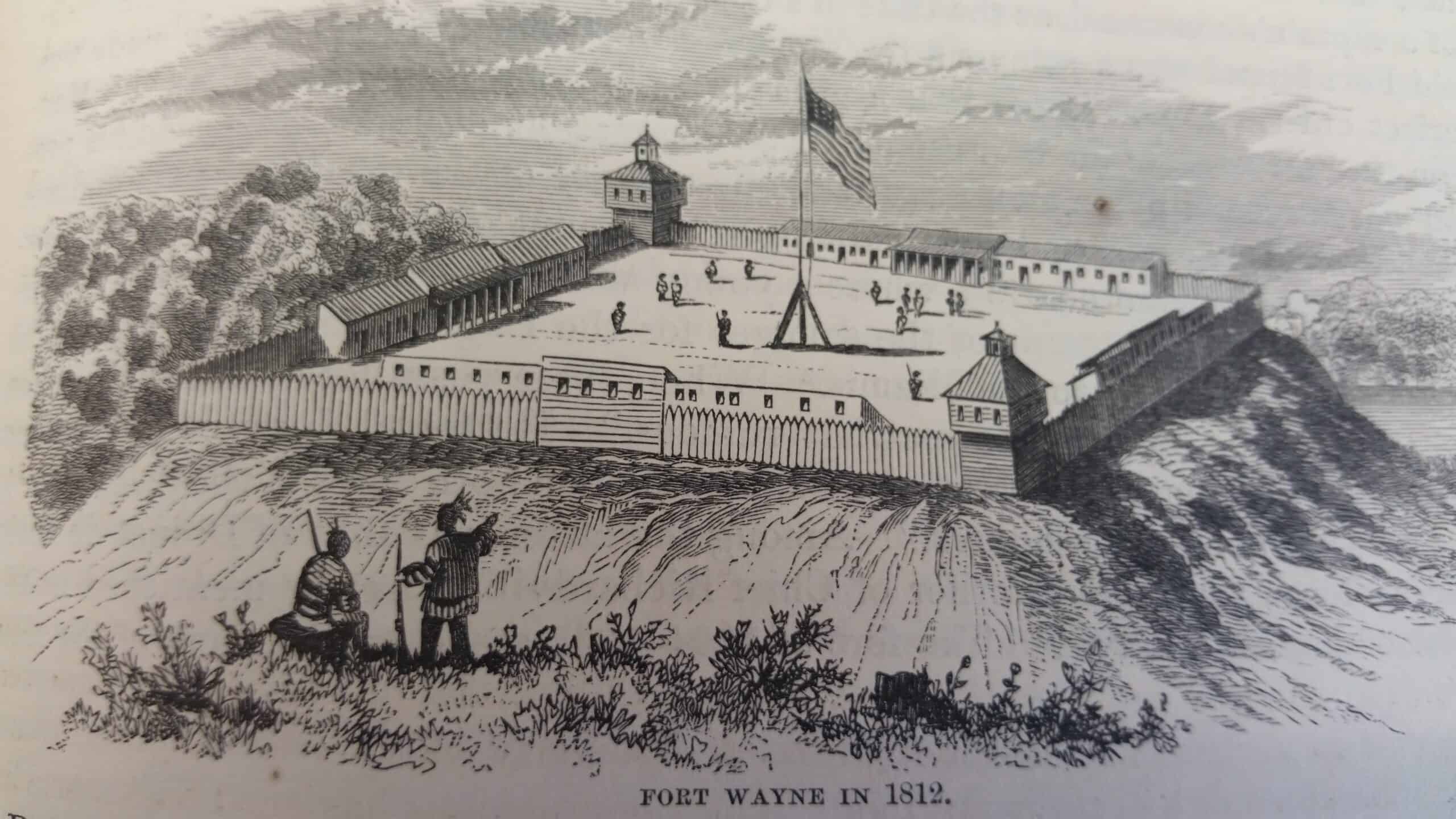

Arriving at the Fort Wayne garrison on September 15, 1809, Harrison began negotiations on what was the most comprehensive of several ongoing land deals. He was there to purchase about 2.5 million acres north of Vincennes. The Shawnee, which had refused to participate, were considered a small remnant and largely ignored despite the pronouncements of tribal leader Tecumseh.

As many as 892 Native Americans—led by the Miami and Potawatomi, and including the Eel River, Delaware, Kickapoo, Lenape and Wea Indians—would arrive over the next three days from points as far away as present-day Detroit.

Harrison’s secretary recorded the proceedings and the seriousness of the business. “The Potawatomi waited on the Governor and requested a little liquor which was refused. The Governor observed that he was determined to shut up the liquor casks until all the business was finished.”

That business included purchasing a tract of land—in whole—stretching along the Wabash River. During the initial greetings, Harrison handed a roughly drawn map of the proposed purchase area to Owl, a Miami chief. Upon receiving the map, Owl is said to have replied, “We are very happy to hear your address. We shall take what you have said into consideration and will return you an answer.”

Negotiations break down as tribal leaders remember British warnings

Not everyone at Fort Wayne was happy to hear from Harrison. By Saturday, September 23, 1809, the Chiefs of all the present tribes met to discuss the deal. It was understood the Potawatomi Chief Winemack was in favor of the sale, as were the Delawares. But according to the interpreters at the meeting, the Miami remained silent.

Remembering a British diplomat who had warned the tribes after the Revolutionary War never to sell any of their lands to the United States, Little Turtle, a Sagamore (Chief) of the Miami, was suspicious.

According to the Journal of the Proceedings, the Potawatomi approached the Miami and Little Turtle to convince them to agree to the sale. One Potawatomi declared, “The Potawatomi had taken the Miamies under their protection when they were in danger of being exterminated and saved them. They had always agreed to the sale of lands for the benefit of the Miamies and they were now determined that the Miamies should sell for their benefit.”

“We have listened to what our Father [Harrison] has said,” Little Turtle replied. “It is true that the Miamies are not united with the Delawares and Potawatomi in opinion.” The Miamies withdrew for the evening to meet with their other tribal leaders, undeterred and aware the hopes of the entire deal rested with them.

Perhaps fearful of western settlers, desiring the cash payment, or just hopeful for peace, the Potawatomi “…poured upon [the Miamies] a torrent of abuse and declared that they would no longer consider them as Brothers” if they didn’t agree to sell. The Miamies, holding firm, reaffirmed they would never consent to sell any more of their lands.

Later the next evening, the Governor met with the Miami Chiefs at his camp. It was Sunday and Harrison, by now frustrated at the pace of the talks, wanted to hear their real reason for not agreeing to sell land.

Little Turtle told Harrison of soldiers at a British outpost years earlier who had told them never to sell to the United States. Agitated at the notion, Harrison spoke of the “perfidious conduct” of the British toward the Americans after the Revolutionary War.

According to one of Harrison’s interpreters, Harrison warned, “In case of a war, the English know that they are unable to defend Canada with their own force. They are therefore desirous of interposing the Indians between them and danger.”

Two days later, Harrison would continue to extol for hours at a time how the United States treated “the red people” significantly better than Great Britain. Speaking to all the tribes for nearly two hours, he added, “A Treaty was considered by white people as a most solemn thing and those which were made by the United States with the Indian Tribes were considered as binding as those which were made by the most powerful Kings on the other side of the Big Water.”

Land deal hinges on a bad $70 debt

Negotiations continued in the warm September air. After a little wine, the Miami and Delaware tribes next tried to push Harrison to buy by the acre, not by tract as Harrison had proposed. The Miami also wanted significantly more money at $2 per acre than Harrison proposed for the whole tract.

“When it is bought in the large quantity you are paid for good and bad together,” said Harrison. Pressuring the tribes to accept a tract deal before he walked away entirely, he added, “And you all know that in every tract that is purchased that there is a great portion of bad land not fit for our purpose.”

Everyone was running low on patience. Negotiations had stretched through the week. Harrison, tired of waiting, announced he would submit a Treaty for ratification the following day on Saturday, September 30.

The Potawatomi Chief began to speak in favor of ratification. But the Miamies, led by Little Turtle, abruptly got up and left the Council House.

Determined not to let the negotiations fail and to find out what the hesitancy was once again, Harrison and a single interpreter set out to meet the Miamies at their camp at sunrise on September 30.

In the ensuing talks, Harrison learned the principal War Chief of the Miamies distrusted a white man.

At issue was a Mr. Audrain, whose first name is never mentioned in the Proceedings. Mr. Audrain had allegedly cheated the Miami War Chief out of $70, presumably in some sale of goods for which he was never paid.

For better or worse, Mr. Audrain was a connection of Mr. William Wells, one of Indiana’s best-known frontiersmen and one of the two Indian agents accompanying Harrison from Vincennes. The Eel River Miami had captured Wells in 1784 as a young boy. Wells would later become a Miami warrior and be a controversial “Indian agent” at Fort Wayne for much of his life with conflicting allegiances between tribes, the British, French, and American settlers.

The Miami War Chief asked Mr. Wells in vain “for redress” on the $70 matter but with no success.

The Governor, writes his secretary, “…had no alternative but to promise immediate satisfaction for these claims and to assure them that he also perfectly understood and admitted that they [The Mississinway Chiefs] were the real representatives of the Miami Nation.” There is no record of who paid the $70 debt.

An agreement is reached to survey by shadow

With Mr. Audrain’s long-lost debt repaid and wine flowing, the evening of September 29 took on a celebratory mood. The Governor had negotiated the sale by tracts and at a price favorable to the United States. He had also managed to strike deals for subsidies and peace negotiations among tribes. With few objections, the tribes were also satisfied with the deal and Harrison ordered his secretary to prepare the Treaty for signatures and marks.

The final price of all tracts would come to about two cents per acre—about $50,000, or roughly $1.1M in today’s dollars.

Still not entirely trusting of white settlers and their surveyors or surveying equipment, Little Turtle managed to extract one concession. Rather than using traditional chains and surveyor marks, they would instead mark the tract by “throwing a spear into the ground at 10 a.m. on September 30, 1809. Where the shadow cast would mark the boundary of the tract.” Harrison had no objections to this unique surveying method.

Every warrior in attendance signed without objection except Little Turtle, who objected to an article giving the Mohicans the right to settle on the White River. The other Miami Chiefs disagreed however, declaring in favor and the matter was settled.

With an agreement reached and a treaty signed—many with “X” marks or drawings of animals for the warriors’ names—the liquor casks opened, and Harrison had his deal.

War and a new political career emerge out of this shadow

The Treaty of Fort Wayne further boosted Harrison’s recognition in the new territories, and agreeing to use the “10 o’clock shadow” method would prove more beneficial to Harrison and Indiana than the Native Americans, too.

In a letter dated November 15, 1809, to F.H. Abbott, the Acting Commissioner of the Office of Indian Affairs, Harrison wrote, “There appears to be much more land in these tracts than I expected, being upwards of 2,900,000 acres.”

In the letter, Harrison included a sketch of land “principally intended to show the advantages which would arise from opening a Road to Dayton in the State of Ohio”. The road would bring much of Indiana 120 miles closer to the next closest state’s capital. “I believe that the Indians would consent to have the road opened through that part of their country which it must necessarily pass through.” The road’s early path would mark the precursor to US 40.

Within two years, encroaching white settlers and lax enforcement of the Treaty led to conflicts and uprisings. More land sales and treaties, including a second treaty at Fort Wayne for a smaller eastern tract of land, were also poorly enforced. By 1810, Shawnee leader Tecumseh had enough and demanded nullification of these and other treaties.

On November 7, 1811, Governor Harrison, with authority from the US War Department, led an attack on Prophetstown, near present-day Battle Ground, Indiana. The attack occurred a day before a scheduled negotiation Harrison saw as “futile” with the Shawnee.

Following the initial rush, Harrison’s men spent two days surrounding Tecumseh and his followers on the Tippecanoe River.

Caught unprepared, the Shawnee held ground against Harrison’s army but eventually lost without reinforcements. After the battle, Harrison’s men burned Prophetstown to the ground, destroying the food stored there for the winter. The tribe was forced to fend for themselves as the militiamen returned home for Thanksgiving.

For decades to come, scores of settlers would continue moving west, essentially displacing the remaining native peoples from their land. When Indiana became a state in 1816, the shadow the spear cast in would-be Putnam County represented a mostly forgotten agreement.

The Treaty of Fort Wayne, combined with the victory at Tippecanoe, pushed Harrison’s popularity to new heights. Early Hoosiers nicknamed him “Old Tippecanoe”, which led to the famous “Tippecanoe and Tyler, too!” refrain during the 1840 presidential campaign. Harrison was elected as the oldest president in history at that time, and the oldest until the election of Ronald Reagan 140 years later.

Perhaps more famously, Harrison, eager to show his youthful vigor, gave a lengthy inaugural address in the cold Washington rain in March 1840. He died from pneumonia thirty days later, making him the first president to die in office and marking his as the shortest presidential term in US history.

Did you find this post interesting? I hope so because it took me about a month to research and write. You can help me do more by becoming a Supporter.