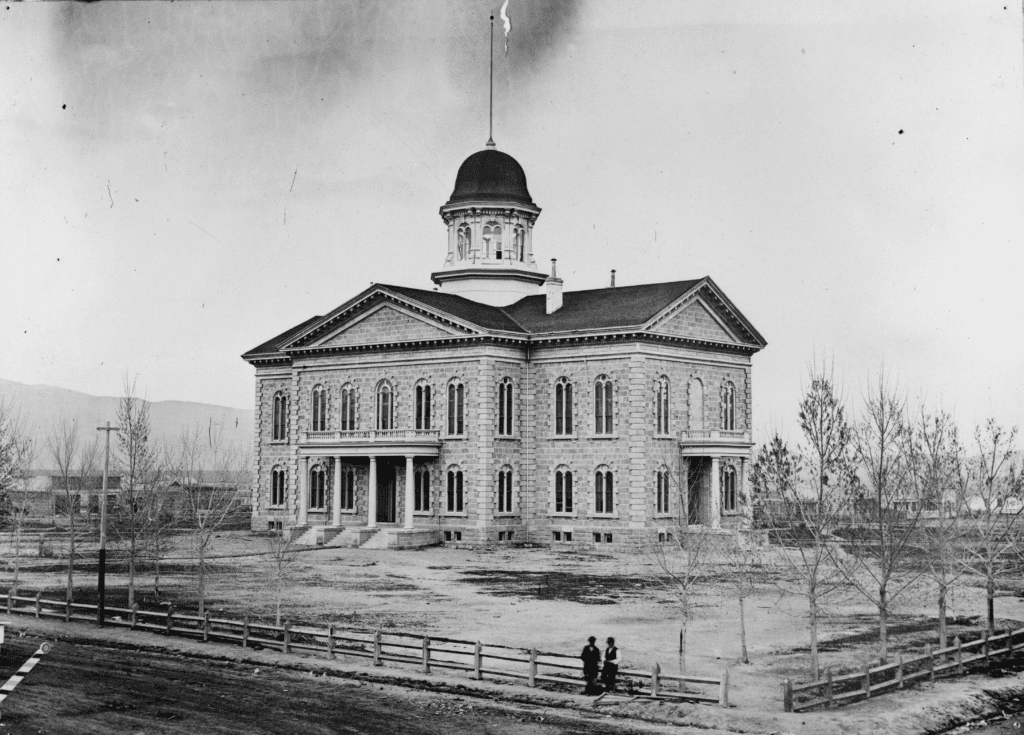

One of these buildings is the capital of a U.S. state. The other is a courthouse in one of the poorest per-capita counties in Indiana, itself one of the poorest states in the Midwest.

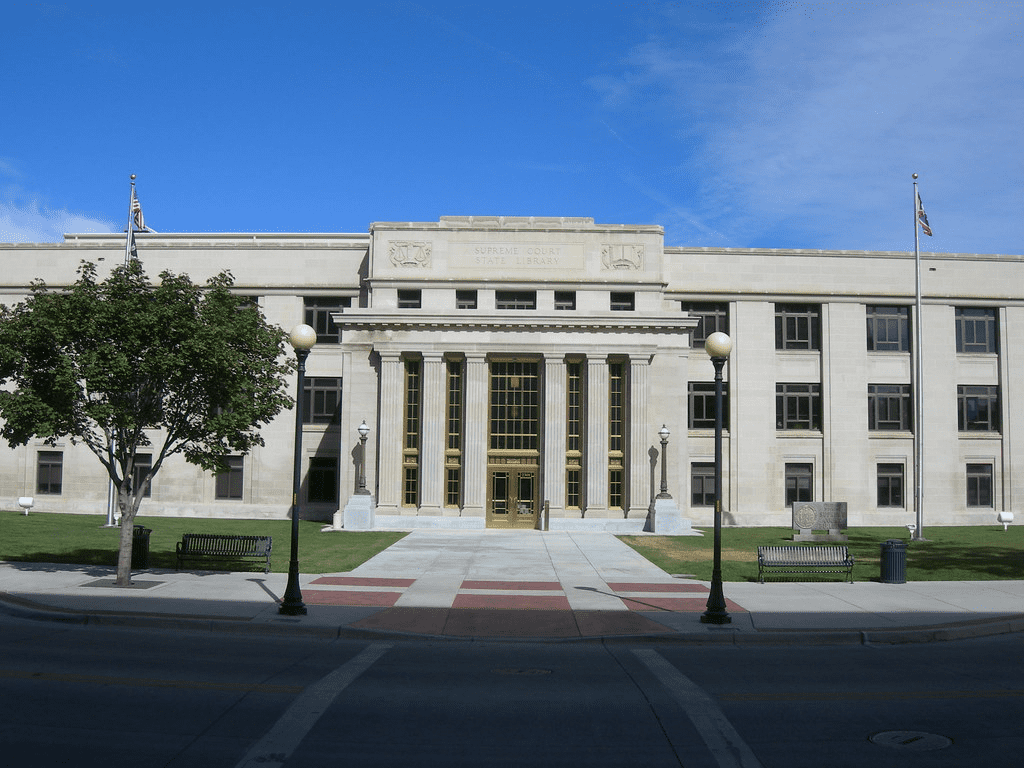

No one can confuse either building for being downright uninteresting, but when you start to recognize the Wyoming Supreme Court operates in a building that isn’t much different looking than some Post Offices and District Courts or county courthouses in the Midwest, like this one in South Bend, Indiana, you start to wonder: how’d the Midwest end up with so many amazingly beautiful bulidings?

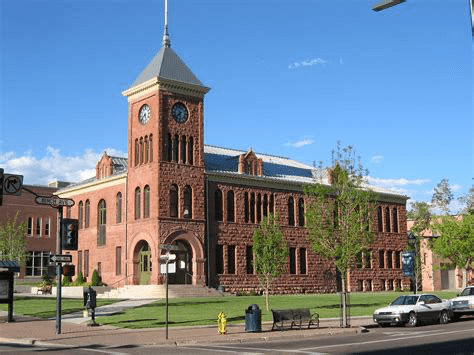

Or compared against the Coconino County Courthouse in Flagstaff, Arizona:

Which is nice, but it doesn’t look much different from some train stations or fire departments in the Midwest.

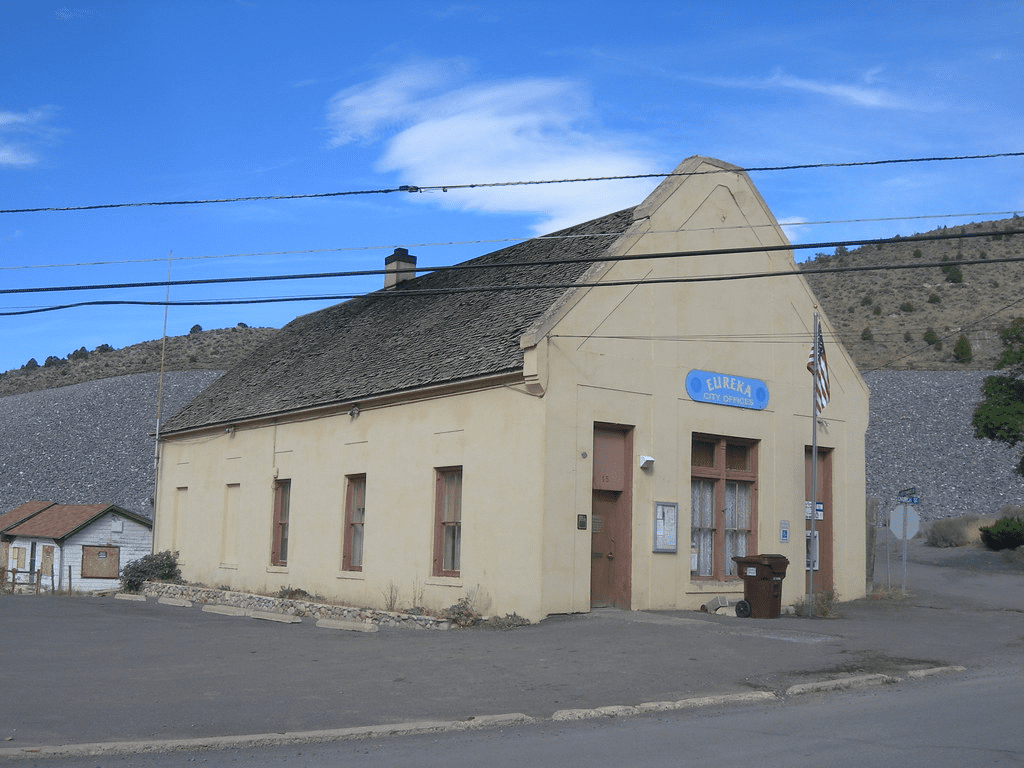

Or compare to courthouses in Mina, Nevada, Nye County, NV, or even the building the Nevada Supreme Court sits in.

Why some things happen and some don’t: it’s usually money

I’ve been fascinated by why some things happen when others don’t — all things being equal. Like, why is Colorado full of 5 million people today when Wyoming has 800,000, despite being roughly the same size with similar ecological, hydrological, geographical, cultural, and meteorological features? Colorado had gold, so it got more people, and thus more people beget more people.

“Follow the money” is good advice to understand why anything is how it is today.

But how do you explain Midwest courthouses, which are opulent, decadent, and completely out of bounds of the scope of budgets today? Heck, Midwestern courthouses were out of bounds for budgets when they were built in the mid and late nineteenth century. They frequently took a generation more to pay off, and construction took almost 30-50 years. They were grand projects.

I’ve been picking on Nevada, but in just about any frontier town the rule was the same: no one expected to be there for long in the initial founding of those towns and counties.

Take Juab County, Utah. The original courthouse looks like a small church, which now serves as a city office building:

A later one looks like a house and now serves as a museum:

Today, Juab County has a courthouse that looks like just about any old high school in the Midwest:

These buildings were designed to function, not persevere

Midwesterners, however, landed in a new area and thought this was a place worth sticking around. A place to grow roots and establish a family, with generations of children that would come after. We built things to last and celebrated our communities with detailed, intricate, and ornate buildings that spoke to our pride. This wasn’t “big government spending”, this was pride mixed with hubris and the desire to recognize our past, present, and future. Somewhere along the way we realized we needed to get serious and move beyond log cabin jails.

Frontier towns in Nevada, Arizona, Utah, Texas, and points west were frequently passed over as temporary stopping points. Towns functioned more like temporary accommodations. Buildings that were the cornerstone of the communities, like courthouses, government buildings, post offices, and schools, were constructed to be nice, but no one wanted to bet the whole farm that anyone would be around in a few decades.

Whereas in the Midwest, we assumed these buildings would still stand in 200 or 300 years.

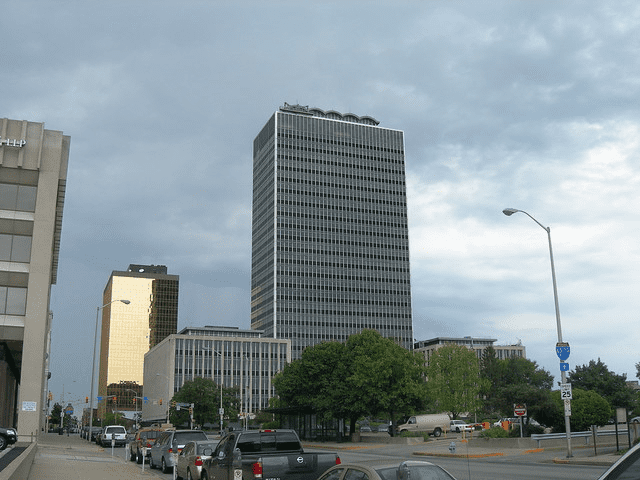

This is what makes the Marion County and Madison County courthouses so tragic. When the Madison County, Indiana courthouse started to fall in disrepair in1964 it was demolished in 1972. The County Commissioners built this in its place:

No offense to architects and designers who enjoy the all-glass, brick, blocky aesthetic, but this is a real shame. This building does not say, “We intend to be here in 200 years.” This is not a building that says, “We are proud of our community, and we are a healthy, vibrant people.” It’s a building that says, “We picked a competitive bid for a building with space for more cubicles.”

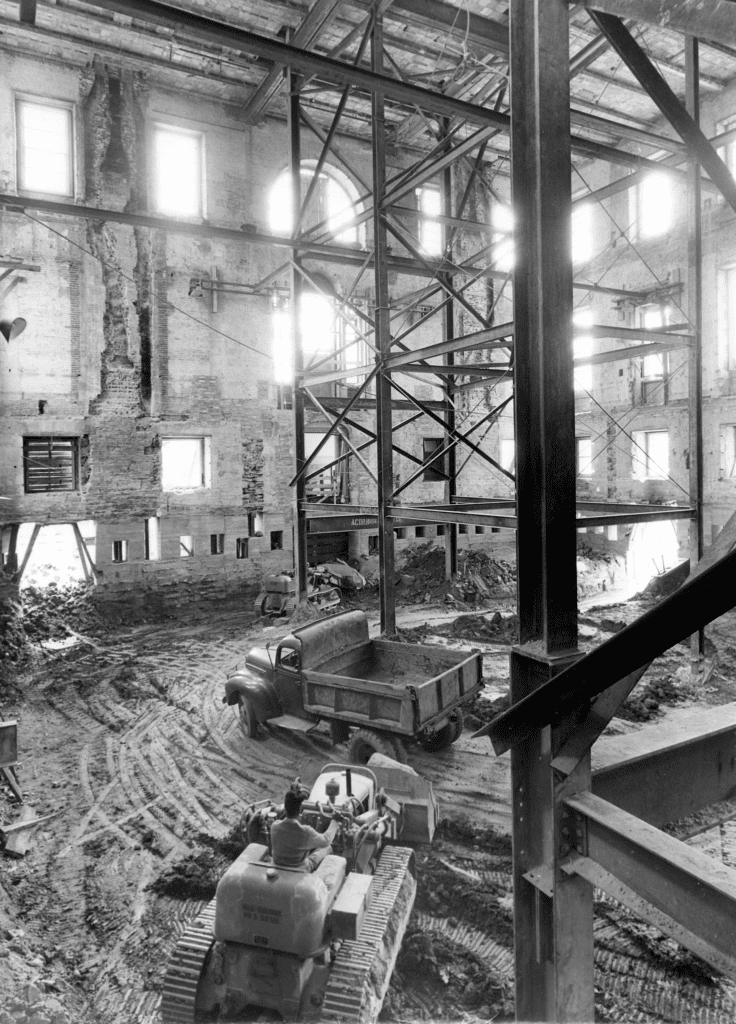

Likewise, in Marion County (Indianapolis), when its courthouse was torn down for the current City-County Building. This building was demolished in the 1970s to make way for a building that, as of 2023, is half-vacant from a new boxy, glass building built halfway across town for the county Judiciary. Indiana Landmarks has a photo that makes me downright upset to look at.

The City-County Building features wood-paneled walls and two smaller, squat buildings, giving this a phallic design. It also needs about $40 million in repairs as the City considers what, if anything, to do with it.

This building does not say, “We are a proud people intent on being here in 300 years.” It says, “Eh, what’s next? And let’s do it cheap.” The 1970s City-County Building has, from the sound of things, lasted about fifty years.

To be fair, Midwestern states’ original courthouses and Statehouses were not always grand. The original Indiana Statehouse was demolished about 50 years into statehood to build something arguably more grand in its place that exists today. The old Illinois State Capitol remains preserved today (likely because of Lincoln’s presence in the halls), but a grander structure sits just down the street in Springfield.

A bad omen for the future

I find this trend worrying. Not every old building has to be saved, of course, but there ought to be a line somewhere, and surely that line stops with the centerpiece building of just about every county in the Midwest. This trend signals a shift in thinking from “Look what we are and will become, even compared to our older peers on the east coast,” to “None of this really matters much; let’s just make it quick and easy.”

Quick and easy is rarely good for anything.

Ball State Economist Michael Hicks has a post on the economic opportunity now present in places with high quality of life. It’s well worth a moment to read. Hicks highlights how regions that took a more long-term view years ago are doing better now and will continue to do better economically in the future.

The Midwest has lost its way. Several county courthouses are now on Indiana’s Endangered Landmarks list. A list that has included and should probably continue to include Washington County’s courthouse featured above. Thankfully, Washington County’s leaders devoted $1M to the project a few years ago.

Other counties have rallied in the right direction. Hamilton County, Indiana gets relatively high marks for quality of life, though Fishers, Indiana, has a disturbing tendency to demolish just about anything in favor of a new art-deco Dairy Queen. They have virtually no historic district connecting them to a past earlier than 1995.

Virtually every county has a Commissioner so wound around conservative bonafides they’d just as soon demolish every public building in favor of a Wal-Mart if the opportunity presented itself. Call me crazy, but the word “conserve” is right there on the tin.

Private foundations in some rural counties often spring up to raise a few dollars to patch a roof or replace a floor in their courthouses, but it’s a slog. Part of the pressure may stem from the belief construction projects should be quick, even the repairs. This fails to recognize many courthouses, as one example, took much longer to build.

This isn’t all about money, but of course, it’s about money. These buildings are expensive, and they are expensive to maintain. It’s also possible local governments have grown because the populations have grown, and they need more space.

I do not believe, however, the answer is demolishing and building a new, squat box. Simply building another building nearby is perfectly reasonable, as Indianapolis has done twice now, albeit by demolishing some old buildings along the way. The Old City Hall remains, albeit totally unused right now. Hamilton County, Indiana smartly built a larger government complex near their Square in Noblesville years ago to reflect their swelling population.

Critics argue these buildings are in disrepair, so out with the old and in with the new (and cheap!). But disrepair is a result of too much short-sightedness. The Indiana Legislature could likely fix every cornerstone public building in the state with its surplus money. Which is odd they haven’t, considering the rural-leaning bias of many legislators. Local leaders could also get serious about raising money, either privately or publicly, but they don’t.

In Washington County, Commissioners heard how the roof leaked and it damaged court and clerk records inside the building for nearly a decade. The basement is surely a mess, and for several years the County couldn’t be bothered to find $5-10,000—the cost of about half two feet of road repair—to replace Christmas lights that hang on the building where Santa greets children each year. The routine excuse is some bridge that connects a dozen people in the netherregions off a gravel road needs a new culvert. Priorities!

When this country was young, John Adams arrived in Washington, D.C. to find an empty swamp with a few beautiful marble and limestone buildings rising in the distance. Despite the grim scene, everyone recognized the need to build something designed to last.

Harry Truman knew full well that demolishing the White House, as was considered to do repairs after WWII, would have sapped national morale as a new Cold War settled in. Instead, the building was gutted with the facade in place so the world didn’t see the country literally dismantled. Yes, it cost more money, but does anyone think that was the wrong decision, budget be damned?

To be fair, the buildings were constructed from slave labor. That dramatically reduces costs, but they were still expensive buildings. Many Midwestern buildings likely used black men to help build them, likely at lower wages than white men. But in many rural Midwestern counties, there were no black men, only poor whites.

It’s also fair to recognize most buildings of the first 175 years of this country didn’t pay much attention to workplace safety, environmental studies, archaeological impacts, etc., that we do today.

Still, politicians have become so vocal about cost-cutting we’re basically amputating ourselves to save face for the short term at the expense of long-term community pride, growth, and quality of life. This strikes me as unthinkable to all but the most rabble-rousing of residents some 200 years ago.

One hundred years ago, the leadership of Indiana celebrated the state’s 100th birthday by forming the basis of our state parks. Brown County, Turkey Run, and other state parks came from this mammoth preservation and conservation project. It was literally done to celebrate the past and preserve something for the future. It was a statement about our values. Brown County State Park is among the best in the Midwest, maybe the nation as state parks go today.

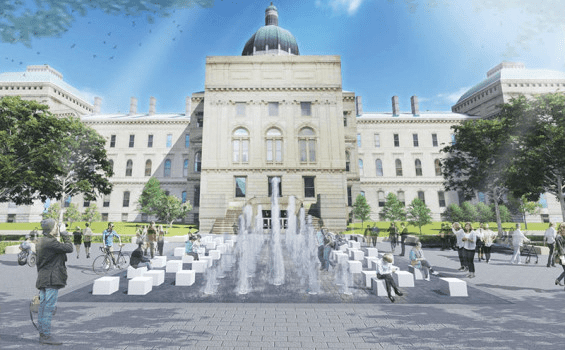

When Mike Pence was governor a century later, our leadership decided to celebrate our 200th birthday with this fountain. This is not a statement about anything except, “We’ve given up.” Most of the time the lights under the lights are never on, and of course the water is turned off during the winter, leaving a bunch of random sugar cubes sitting on the ground sandwiched between the Statehouse’s back door and a parking garage.

A sign of health and quality of life

Does a courthouse improve quality of life? Maybe not the same way a crime rate impacts life. But visit any county in the Midwest and everything from the seal, letterhead, newspaper, website logos, sports teams, and more probably have some play on their courthouse as a central figure. Does this fountain plaza squirting water in the air for five months of the year improve quality of life? I’d argue not, and suspect most would agree.

We’ve lost our way in thinking about big, grand, adventures. As if the only thing left to pursue is nothing at all.

County and state leaders need to get serious about protecting what our forefathers and foremothers worked so hard to build for us. We’re like children who inherited an expensive new bicycle from grandma and instead of using it responsibly, we let it sit out in the snow all winter—rusting and rotting all to pieces.

Residents would do well to understand our history so we can better understand our future. When a building is proposed for demolition to make way for a CVS, you really have to ask, “Is this really great for the tax base like these hucksters claim?”

We shouldn’t just demand our elected leaders consider big, grand projects. We deserve it, not just for ourselves today, but for our future residents. The sort of thing that says, “We extended ourselves, and look what we accomplished. It has paid dividends to our morale and well-being than anything we ever could have imagined.”