When Henry David Thoreau spent his eponymous time at Walden Pond, he wrote: “I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived.”

I’m not sure we thought about moving to Michigan with quite so much depth, but like a lot of people who muse about moving off into the wilderness, it was part of the equation. Now, after nearly a year in this pleasant peninsula, it seems reasonable to think about what this change has meant and how living in Michigan as a native Hoosier has worked in practice.

For context, I grew up in southern Indiana. Then I lived in Indianapolis for about twenty years. A lot about me changed in those twenty years, like my views on the Standard American Life (SAL), politics, and how a person relates to the world. The idea that a person can just up and move to the woods, be one with nature, and live a simpler life is more romanticism than practical action. For us, we actually made a go at it.

To be clear: we moved to northwest Michigan in what I’d call “a rural area outside a small beach town.” It’s hardly “wilderness”, but certainly compared to an urban environment it is. For us, it was a step “down” or “back” to well water, a propane tank, and far fewer municipal amenities.

But as anyone who has lived in a small town and a big town knows, living in a small town has a certain richness to it that is unmatched anywhere else. Especially when you can insert yourself into the area.

Big ideas and Mike Pence’s fountain

In April 2023, I wrote about why Midwestern courthouses are so ornate, architecturally interesting, and centerpieces of nearly every county in the Midwest. The gist is because everyone who lived there in the 1800s thought these were places worth staying in, building up, and establishing roots. The lack of OSHA regulations and environmental studies did not make them any more affordable to build. They were expensive, sometimes crushingly so. And when they burned down — a real risk, even from lightning — they’d rebuild.

For a long time, people thought about long-term benefits for their community. The national id was that local sensibilities were tied to the community at large, while national sensibilities were tied to individualism. These two forces co-existed for over a century.

As one good example, come 1916, the people of Indiana decided to celebrate their centennial by establishing a state park system. This was no small feat, since Indiana was one of only a handful of states to consider and execute the idea. For most states, it would take FDR’s administration in the Great Depression to buy up huge swaths of land in fire sales and give it back to the states to turn into parks. Indiana was truly ahead of the curve here.

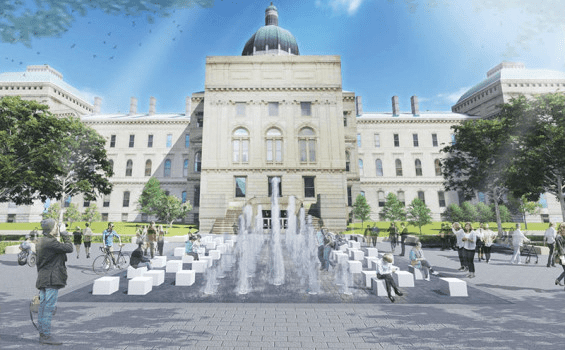

Then, for the bicentennial, Mike Pence led the state to create a fountain.

I wrote:

Still, politicians have become so vocal about cost-cutting we’re basically amputating ourselves to save face for the short term at the expense of long-term community pride, growth, and quality of life. This strikes me as unthinkable to all but the most rabble-rousing of residents some 200 years ago.

One hundred years ago, the leadership of Indiana celebrated the state’s 100th birthday by forming the basis of our state parks. McCormick’s Creak, Turkey Run, and other state parks came from this mammoth preservation and conservation project. It was literally done to celebrate the past and preserve something for the future. It was a statement about our values. Brown County State Park is among the best in the Midwest, maybe the nation as state parks go today, and came along a short while later.

When Mike Pence was governor a century later, our leadership decided to celebrate our 200th birthday with this fountain. This is not a statement about anything except, “We’ve given up.” Most of the time the lights under the water are never on, and of course the water is turned off during the winter, leaving a bunch of random sugar cubes sitting on the ground sandwiched between the Statehouse’s back door and a parking garage.

Not many fountains, not centerpieces to adorn all of Indiana’s 92 counties. Just one fountain. I believe there was also a traveling buffalo statue that people could take selfies next to, a riff on the state’s seal. And there was a torch (a riff on the flag) that got paraded around the state like the Olympics. If someone asked me, “When did things go off the rails in Indiana?” this is the moment I’d point to. This fountain and the lack of far-sightedness is, to me, the “jump the shark” moment in Indiana’s history. And no one noticed it.

Some people laugh at me for it, but the last straw came many years later when my neighborhood in Indianapolis just kept willy-nilly cutting down trees, leaving horrid stumps that would last longer on this earth than Mike Pence’s fountain. This was the point of cogent recognition that Indianapolis is just a very ugly city incapable of escaping the budgetary and cultural spiral it is in. To be clear: Indy means a lot to me. Many of my friends are there. I graduated from IU there. The ugliness is not from the people or the character, but from the aesthetics. It sounds shallow, but our relation to the world around us matters. I like and appreciate when things look nice. When Lyndon Johnson spoke about his interest in the environment, he said:

“[Conservation’s] concern is not with nature alone, but with the total relation between man and the world around him. Its object is not just man’s welfare but the dignity of his spirit. Above all, we must maintain the chance of contact with beauty. When that chance dies, a light dies in all of us. It is our children who will bear the burden of our neglect. We owe it to them to keep that from happening.”

This is the kind of conservation and conservatism I subscribe to.

So, we moved. “Michigan seems nice. Let’s try there.”

A culture of parks and embracing winter in Michigan

Michigan’s special gift is space. Space that seems to wrap around you and heal you. Or kill you.

Regardless, Indiana lost its culture of parks and shared spaces. What was a mammoth undertaking in the early 1900s that yielded places like Brown County State Park gave way to economics, agribusiness, and the undercurrent of the kind of toxic libertarianism that pulses through the state’s history (see also: Doug Masson on Indiana’s history with school funding and its years-long generational delay.)

Imagine my delight to learn that Michigan has 103 state parks. Some 36% of the land in Michigan is dedicated to a park, including federal forests. Indiana has 24 state parks and some federally managed forests, but the total land area percentage is closer to 9%. In other words, Michigan has more parks than Indiana has counties.

This culture seems to be driven by the Great Lakes. Something about them must have been spellbinding for early settlers who rightly recognized that their splendor must be cherished and conserved. To say nothing of the hunting, fishing, and farming operations that dot the region. Michigan produces 300 varieties of food, second only to California. To say nothing of 1,300 miles of coastline that is second only to Alaska.

This geographic good fortune has contributed to a sense of pride and access to the outdoors — in all seasons — that does not fly in Indiana.

Upon moving to Michigan, everyone south of any point of Michigan will remark, “Isn’t it cold?” Yes, but so is the rest of the Midwest. The difference seems to be Michigan’s more temperate climate, thanks to the lakes, which act as a big heat sink. Still, the snow is quite lovely. You remember snow, right? The stuff that fell in our childhoods before the earth warmed to unholy levels?

It turns out when you have real winter, you can embrace that and kinda enjoy it. It’s pretty, and not “a bunch of dead, wet leaves.” I was reminded this year that winter has more colors to it than just brown.

All this to say, nature’s randomness shows gracefully. Everything seems orderly without feeling suburban. Here in Ludington, the town of 7,000 is no bigger or smaller than my hometown of Salem. But it feels so much more interesting, sustained perhaps by the tourism that flows here in the summer. Michigan is certainly a climate haven, for now. And I noticed this week that the a few trees that had died were removed around town. The stumps were removed with a few weeks and neatly padded over. New trees have already been planted nearby. It’s not like one place has a tax base that’s extravagantly larger than the other. It just seems like values to me.

When it rains, it feels clean. When I see a stream, I do not immediately have to question, “Is that safe to go near?” I’m sure they exist, but here in northwest Michigan, I have never seen a body of water of any size that cannot be waded into or, with some processing, consumed.

Bucking the Standard American Life

We downsized to move. This is hard for a lot of people, but as anyone knows about me, I’m keen to reduce and favor fewer things. Less time cleaning and replacing, less time maintaining, and less time spent fussing with things is a life worth living.

I think it’s fair to say most people are temperamentally not prepared for ridding their closets, garage, and myriad kitchen drawers. Loss aversion is real.

Further, there is a cultural sensibility that has to change. I miss some things, like being able to get around on a bus in the winter or having a huge library. These things exist in small towns, sure, but they are much smaller. The library here seems designed more for kids and teens. Which is fine, but means I end up buying more new and used books than I used to.

There’s also a political sensibility. Michigan is a relatively purple state as these things go, but you absolutely notice people’s politics in ways urbanites rarely do. And some people are not equipped to deal with that, either. The “I never want to see a gun, a red hat, or a pickup truck” crowd would struggle in most places of the country, not just here.

I’ve felt somewhat conflicted about moving at all because of Wendell Berry’s treatise that people should really make an effort to put down roots and stay put barring major life changes or opportunities. His thinking is you can’t really be in a place until you’ve been there for decades.

Still, Michigan has a lot going for it. There’s a sense of “enough” here. Something about Indiana and most cities seem focused on “more.” More growth, more industry, more business. The assumption being more industry means more income and more taxes and more growth and more … work? I guess?

I don’t hear a lot about economic development here. It seems that most consider that something that will take care of itself as markets do. Instead, the focus feels more on what can be done within a place with what’s here and who is here. There’s a heavy focus on recreation. People seem to like living here? Which is weird to say because I don’t know too many people who felt that way about Indiana. People liked living near their friends or family, or maybe liked their neighborhood within the scope of Indianapolis. But overall? I dunno. This hits different here. There’s a sense of enough.

Maybe Michiganders are, like Thoreau, culturally attuned to the notion that when they die, they do not want to sense that they had not lived.