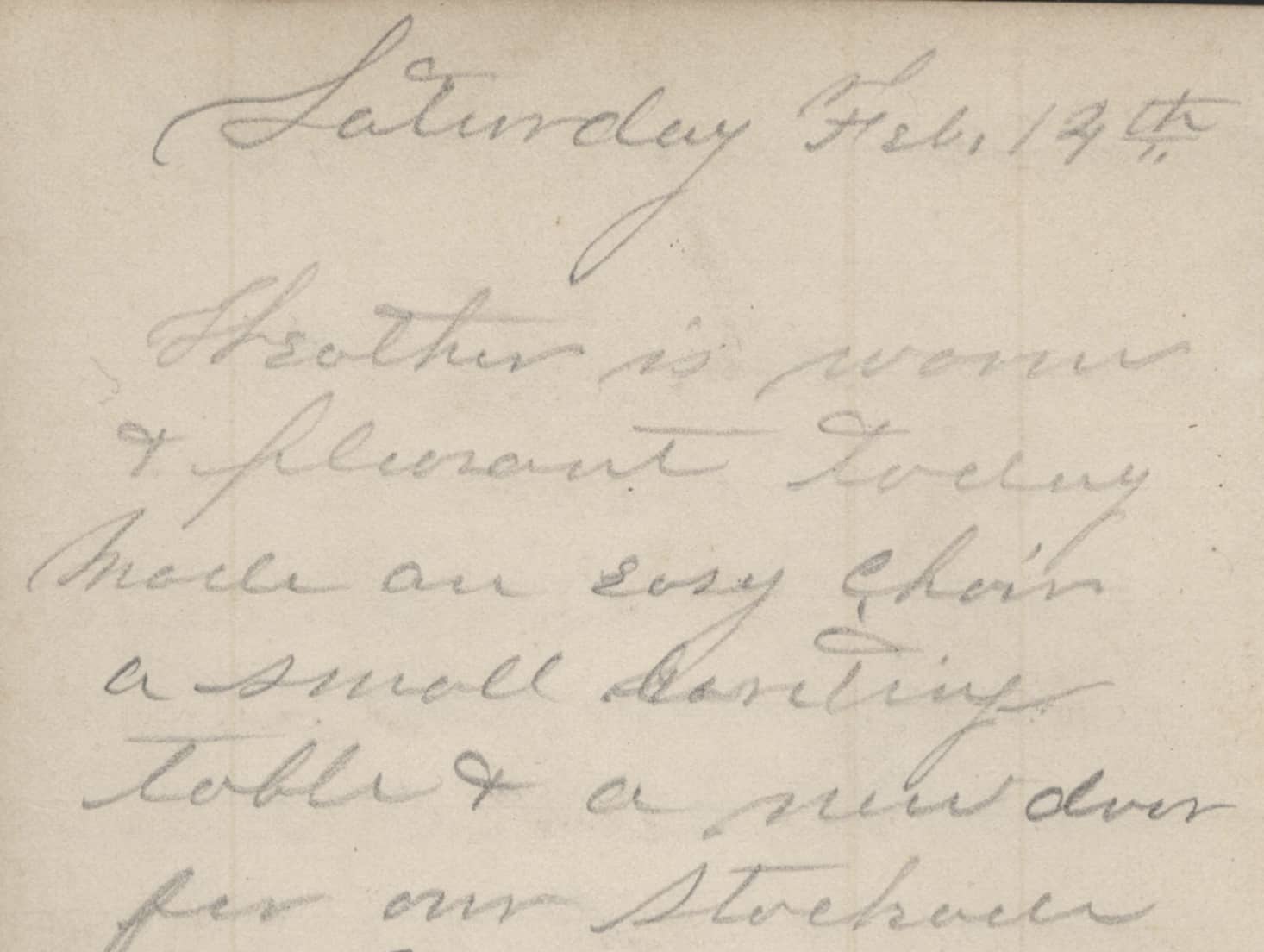

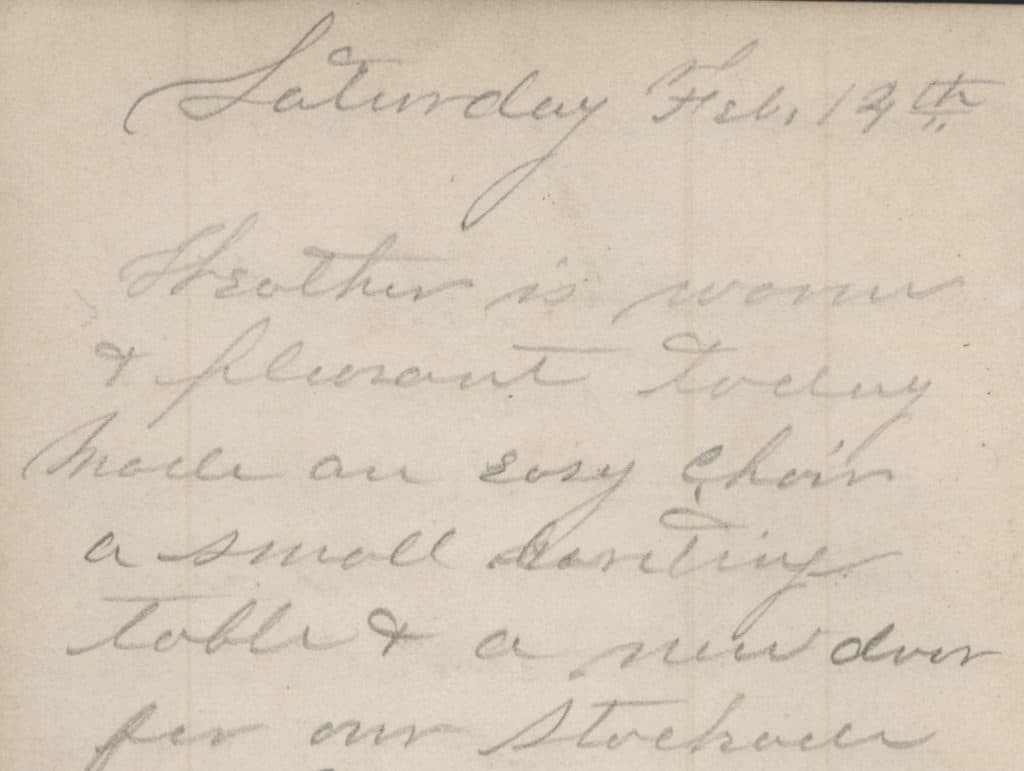

Saturday, Feb. 14th:

Weather is warm and pleasant today. Made an easy chair, a small vanity table, and a new [?] for our storehouse.

Here’s but one entry from a diary left by A.J. Thompson, from Newport, New York. He was a soldier in the American Civil War and served as a part of Battery H, 1st Ohio Light Artillery, Army of the Potomac.

Think about that for a second: here’s a 161 year old piece of paper telling us what this guy did nearly every day.

Meanwhile, a client of mine died last November. She was 91 and wrote a blog at a website that will go offline in 30 days. Her son decided not to renew the domain name, so the years of stories, posts, and book drafts sh has in there will go with it.

This has been surprisingly unsettling to me. We know what Ben Franklin did on almost any given day of his life 250 years ago because he wrote it down. And while plenty of journals and diaries have fallen away to disrepair, water damage, fire, or loss, we know a surprising amount about what our ancestors think and did. And not just in white, American culture but across all sorts of cultures and civilizations.

Given how much we post to Facebook, text, email, and produce online today it’s easy to think future historians are going to have a trove of stuff to work through. But the reality is much worse.

The Library of Congress archives all tweets (yes, even yours!), but almost nothing else from everyday individuals is archived. The Internet Archive has the closest record of the Internet, but it’s sorely lacking with broken images, links, and incomplete pages.

Archiving the Internet is a bit like a trip to Mars today: we know how to go about doing it, but huge challenges in logistics, time, cost, and technology remain.

You may not care about the loss of one blog anymore than you care about this guy’s 1860 diary. But would you care to read your great grandmother’s diary? Or your great great grandfather’s? Researchers know no one cares about anyone else’s family story, but everyone cares about their own.

Our digital longevity is remarkably short. Our Facebook posts last only so long as Facebook is a company that maintains it and people still visit it. Our websites last only so long as someone pays the domain and hosting bills and maintains them from falling into disrepair from hacks, failures, errors, and the forward march of software upgrades.

Never have so many photos and videos been taken of people and things all around us and almost all of them will die with us. If you died right now, does your spouse or family know your iCloud or Google account password? Do they know your phone’s PIN? Do they know the passwords to your 2-factor Authorization apps or password managers? Most likely not.

That means when you die, all the photos in your phone are forever tied into the ether. Even if your next of kin did know the logins and could get at the photos, what would they do with them? It’s challenging to transfer thousands of photos. They’re not likely to be printed, either, even if you picked the best of the best.

A website’s domain name can only be registered for a maximum of 10 years in advance. Website hosting is almost impossible to predict or pre-pay for more than a few years in advance. Even this site of mine, where I’ve been writing since I was in middle school, will likely fall away into nothingness.

That’s problematic for future historians and researchers, but also our families. Our emails are voluminous and yet unlikely to be stored forever. Everyone recalls the account they used to have, or a past employer’s inbox, or the time you gave up on the spam and just made a new one. Even internally at organizations looking to save money email isn’t saved for more than 90 or 180 days, maybe a year.

“Yeah, but who would want to read all my email?” you ask. Probably few people. But your grandkids likely will when they’re old enough to appreciate you and their past. They may come to appreciate understanding what you went through, how you felt, your moods, and to get an idea of your talent, skill, and personality. “Huh, I guess grandpa was a lot like dad in the way he liked to engineer solutions to problems,” they might say. “Great-grandma was kinda sassy to people, wasn’t she?”

I wish I could say I have a solution to this problem, but none exists. The best we can do to leave a footprint is to write things down on paper, preserve our journals and notebooks, include our passwords and PINs to our email and data accounts in our wills, and consider our digital longevity before we’re gone.