I had the rather unusual distinction of being the second jury pool to be called into the new Indianapolis-Marion County Community Justice center in May 2022.

I used to work for the Judiciary, so elements of jury service and trials are not new to me. I had been called once before many years ago, but never made it to the jury box. This was my fate again as I got called, sat in a courtroom, but never questioned by the defense or State.

Generally, the experience works like this:

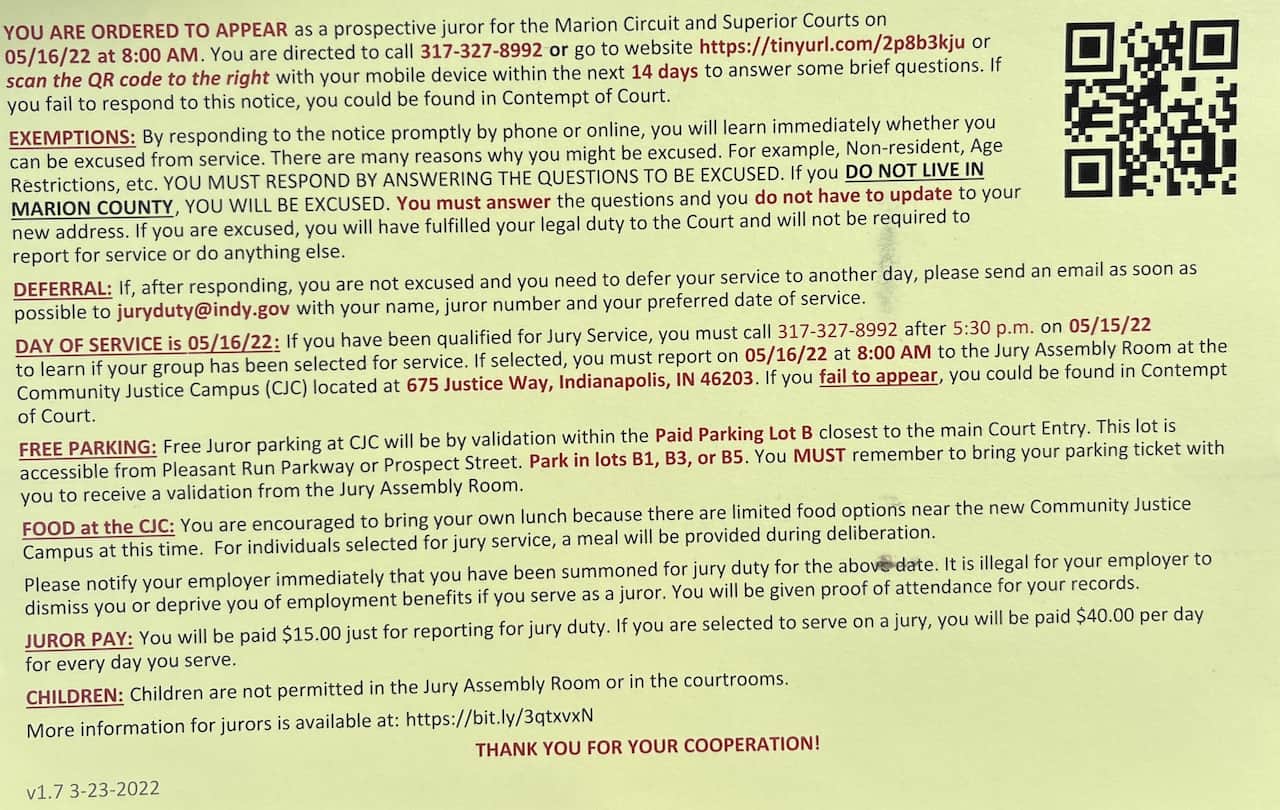

- You get a bright yellow card in the mail. It almost looks like a scam credit card offer at first glance.

- You’re told to answer an initial questionnaire to weed out people who don’t live in the county, are dead, unable to read and write in English, etc. Do this on a laptop because the website is ancient and won’t work on a phone.

- You’ll call a number the night before jury service to find out if you’re called to appear at 8am the next morning.

- When you come to the CJC, you’ll go through security. It and the style of the building are very much like an airport, right down to the kinds of seats they have floating around the halls.

- You’ll go into a Jury Pool room. It’s large and seats probably about a hundred people. This is where you’ll sit and fill out a slightly more in-depth questionnaire. Much of it is designed to get at whether you might be biased in a criminal case (e.g., you have a lot of family in law enforcement) or have conflicts of interest in civil cases, which almost always involve insurance companies.

- You’ll continue to sit and wait for about an hour to ninety minutes. Thus, there is no incentive for you to arrive early at all. Eventually they will play the “Jury Service in Indiana” video at around 8:40. It’s 17 minutes and so old I remember working on parts of it when I was at the Court. By now it’s ancient and not widescreen, plus the audio drifts out of sync with people’s mouths, and they’ve tacked in bits to accommodate things like cellphones and Facebook having been invented.

- Staff from two or three courts will come in and read everyone’s names they want to collect questionnaires from. This process is cumbersome because the room is large, they’re hard to hear sometimes, and people’s names are challenging to read or discern from people with similar-sounding names. This process starts right around 9:10.

- The staff will disappear for about 15 minutes while the courts add people’s names to a computer system that randomizes who is selected and in what order to sit in a jury box.

- The staff reappears around 9:30 and large groups of potential jurors, about 36-40 in all, will go upstairs via a series of elevators to a courtroom. This process is very cumbersome because it was clear no one designed the building for this. The hallways in the CJC are suspiciously narrow at times, the elevators aren’t large enough to fit all the jurors, and the upstairs halls are somehow even more narrow with enough room for 1.5-2 people to fit side-by-side.

- People enter into the jury box 14 at a time, the remainder sit in the gallery at the back of the courtroom.

- The prosecutors and defense attorneys take turns questioning the jurors about their questionnaires after the judge asks some clear questions about, again, whether you’re a felon, have medical conditions, etc.

- After each side has questioned jurors, they confer quietly to decide who to strike. The first set in my cohort lost about half, as did the second, which got them 12 jurors and 2 alternates. I was in the third cohort and never got called to the jury box.

Some observations and notes about Marion County’s jury process

- The jury summons card sent to people is so…angry. They’re constantly YELLING IN ALL CAPS and writing things in BIG BOLD LETTERS. The QR code leads to a page that isn’t very helpful if you don’t know what you’re doing and the bit.ly links they include have cumbersome URLs that, truly, would just be easier if the said “go to indy.gov/jurypool/register” or something similar.

- The building is in the most frustrating location for anything but a car. There is bicycle parking, but biking there is a nightmare of road closures, particularly from the east and north currently. There is virtually no bus service, save two shelters (one coming, one going) for routes 14 and 26. The 14 has hourly frequency, the 26 comes every 90 minutes. I live all of 5 miles away and the bus journey mapped out to just over an hour. I’m incredibly salty about that. Even if you walk there, the parking lot is vast and winding—the complete opposite of what we’re supposed to be building as transit-oriented development. By this measure alone, it’s hard not to argue jury service is a kind of regressive tax on people’s time and money.

- The staff are incredibly nice and thankful. It’s obvious everyone from the judge down to the receptionist at the front desk knows no one wants to be there.

- It’s also obvious they know their $15 payment for showing up—which comes in “two to three weeks”—and the $40 you get per day you serve as an actual juror, are laughably small. Judges have been complaining about this for as long as I can remember. Some, like in Hamilton County, have (at one point) tried to assuage this with doughnuts and coffee. In Marion County, there’s a canteen where you can buy some Skittles and overpriced water. Again, a bit of a regressive tax.

- They encourage you to bring a lunch, but be aware there is no place to store or heat it. So pretend you’re in first grade and have to go on a field trip.

- The whole building feels weirdly cheap in ways. The floor had rubber matting that was buckling with odd dips. Even weirder: the floor sits at a slight incline down the hall. If you set a marble down on one end, it’d roll to the other real fast.

I joked that if I have to serve, “I want something big.” And lo, I was there for a murder trial. You will see the defendant in a criminal case, and he or she gets to confer with his attorneys over who sits on the jury.

There were some overly chatty people in my jury cohort. They were struck. So were the people who nervously giggled and said things like, “I don’t know, maybe?” a lot. You’ll never know why you were struck—it could be a conflict of interest, it could be because of something you said or a medical issue you might have. Or, frankly, the defense might not like the idea of another white person on the jury or the prosecution might not like you have such cantankerous views about hypothetical situations.

Both sides will, however, put each juror on the spot for a few moments to ask pointed questions like:

- “What kind of evidence would you expect to see in a murder trial?”

- What would it take for you to believe a person in a hypothetical bank robbery is guilty?”

- “What does ‘reasonable doubt’ mean to you?”

- “What does ‘circumstantial evidence’ mean to you?”

- “If I told you someone’s shoes were black and someone else said they were navy blue, do you think that makes a difference in the case?”

For many of these questions, the answer is always, “It depends”, but that’s what the attorneys are trying to suss out.