Scientists have a lot of ways of defining and measuring weather events. Meteorologists can define a storm’s wind speeds, forward progression, gusts, and sustained winds — all measures that are roughly the same category of “wind.”

As a Good Midwesterner, I’m interested in tornadoes insofar as the threat of tornadoes is ever-present. Watches and warnings are common, but most Midwesterners rarely see a tornado. Even fewer experience them directly. I have witnessed one once, and luckily from across a distant field.

Unlike earthquakes to Californians or hurricanes to coastal dwellers that cover large swaths of geography at a time, tornadoes are inherently localized. As weather events, they are usually hyper-local, spawning and touching down for less than a minute and statistically well under a mile, if that. Only about 10% of tornadoes are rated as EF2 or higher, and the vast majority of those don’t stay on the ground for long.

But it’s hard to live under the threat of tornadoes for your whole life and not wonder: “What’s the worst tornado ever?”

Like most meteorological events, that distinction is challenging to define. A Wikipedia rabbit hole sent me down the path. Tables abound online of the “worst” tornado in specific states or regions of the country. There are measures of peak wind speeds, duration, distance, communities hit, and number of outbreaks.

Defining “the worst” tornado requires you to break out scenarios and make distinctions most people reasonably disagree with:

- If a storm system spawned a tornado that touched down 3 separate times in the span of 5 miles, is that “worse” than a storm that spawned 3 separate funnels that touched down across 1 mile?

- If a tornado is on the ground for a few minutes across 3 or 4 miles and reaches a peak wind speed of 200 MPH is that “worse” than a tornado on the ground for 20 minutes across 30 miles that reached 150 MPH?

- If a monster EF5 tornado tore across a series of farms and open fields for 15 minutes is that “worse” than an EF3 tornado that hit a series of populated cities and towns across 30 minutes?

Most people reasonably assume the worst tornado is whichever one impacted their lives the most. And most people would argue any tornado that kills people is automatically worse than one that doesn’t. Power becomes irrelevant when lives are at stake.

The arguably worst tornado ever stood out

Tornadoes strike various places on the planet, including in Indonesia, Germany, Canada, China, and the United States. Because of the unique wind flow off the Rockies and the position of the Gulf of Mexico, the US sees a share of tornadoes that far outpaces the rest of the world. And the worst in U.S. history stood out: the Tri-State Tornado of 1925.

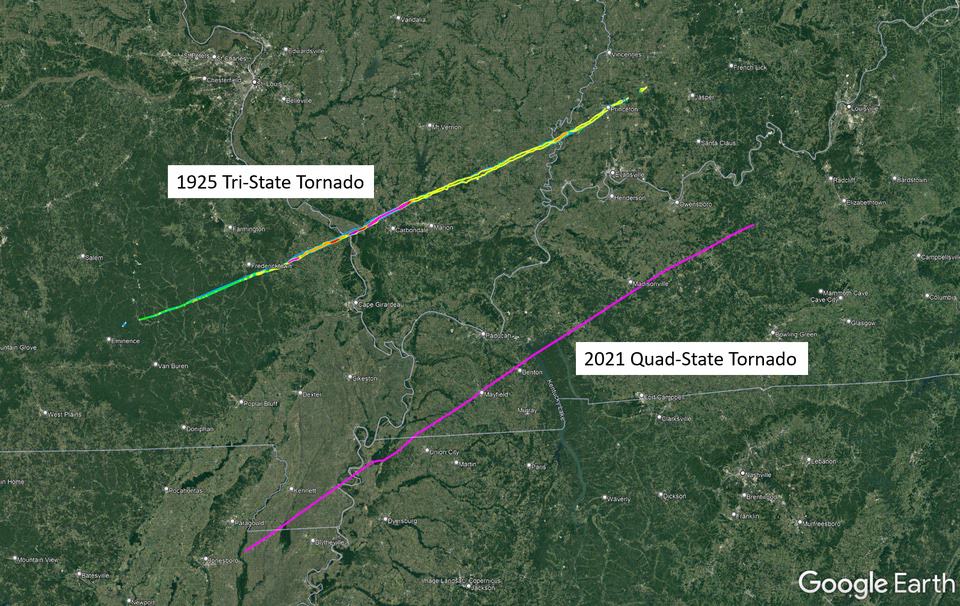

It was large at a mile wide, long-lasting for 3.5 hours, powerful at winds in the F5 scale and had strong sustained winds, came with a torrent of hail and lightning, hit multiple cities and towns across three states, killed 619 and injured thousands, and trekked over a wide area 219 miles long.

I say “arguably worst” because Reddit threads and Twitter-weather-watchers still debate this tornado.

No one doubts the injury count, but many aren’t convinced the tornado was on the ground for 219 continuous miles. One Reddit user posted a now-deleted comment that I can still remember verbatim: “If the Tri-State happened today it’d be called the “Tri-State supercell and tornado family.”

I wanted to know more.

- How had I lived in Indiana all my life and never heard of this?

- How is it possible no one I spoke to ever heard of it?

- How did people respond?

- Why didn’t they see or notice it coming?

- Why was this so debatable about its strength and duration?

- What does science tell us about this storm?

- Was it one tornado or multiple tornadoes that strung together?

There were a few books on the subject, but they weren’t the narrative nonfiction I sought. I expected a book like Erik Larson’s Isaac’s Storm. What I found were books that included oral histories of survivors — mostly children at the time who recalled the events some 60 years after it happened. Others were journalistic accounts traveling across the region searching for clues or talking to survivors, again, some 60 years after the fact.

I know that anyone remembering an event — even a seminal event like the Tri-State Tornado — 60 years later and from the perspective of a 10-year-old is not wholly accurate or detailed. How much do you remember a big storm from when you were 10?

Writing the book I wanted to read

Of the handful of books written which are part of a vital historical record, I wanted something more. I wanted to know more than when a tornado struck a certain town and how many people were injured or killed. Ever since the movie Twister the notion of explaining a bunch of mangled buildings isn’t even all that interesting. At least among Midwesterners, we know what a tornado does.

So, I set out to write the book I wanted to read. Yesterday, September 26, 2023, I submitted my draft manuscript to my publisher.

- I twice traveled into parts of Missouri, Illinois, and Indiana struck by the storm nearly a century ago.

- I poured through state and local historical societies, universities, and stacks of clippings and records from dozens of libraries.

- I read hundreds of newspaper reports from before, during, and after the storm.

- I spoke with meteorologists.

- I read every existing book, which is only about four or five.

- I discovered, scanned, and compiled over a hundred photos — many of which were compiled from glass negatives. At this point, I may have seen every photo taken from that day that still exists.

- I looked at modern data-driven computer models of the conditions that day.

- With the help of researchers at Purdue and the National Weather Service, I was able to get information on temperatures, rain fall, and winds recorded at utility plants along the storm’s path.

- I read research journals and reports on the storm from both that era, the 70s, and as recently as 2010.

- I initially drafted over 75,000 words that I’ve since trimmed to just under 50,000.

I wanted to know more about the recovery — something virtually no existing book discussed.

I wanted to know how the government responded and what issues people endured long after the storm.

I wanted to know what kinds of fear, heroism, and the details of what people faced during and after the storm.

I even wanted to know what some people did before the storm.

I came away with scores of stories, some complete and some a mystery lost to history. I came away with what I believe to be the most thorough account of the recovery efforts available today.

There were documented accounts of heroism, rescues, immense misery and sadness, and a mammoth global response that people living in the affected communities hadn’t even heard of. When I spoke to people in local historical societies who said, “Wait, really?” I knew I was on to something new and valuable.

To people who live in the impacted area, especially around Murphysboro, Illinois, The Great American Tornado as it was called is an important part of their history. So much so several people I spoke to referred to it almost as if it was part of their identity, and rightly so.

The damage from the storm was so severe and devastating that the economic impact is still noticeable today. In fact, I recently discovered that when you adjust for inflation, Illinois’ overall average of tornado-related costs far outpaces neighboring states like Indiana but is among the highest in the nation. I discovered that the 1925 Tri-State Tornado was so expensive that, even 100 years later, it still distorts Illinois’ average loss values.

Virtually every weekday for two years, about two hours a day has been blocked on my calendar and devoted to reading, researching, and writing about this tornado. A little progress each day has added up to a complete book that tells the human story of suffering, resilience, and recovery.

I was also able to look closely at the science and what we know about that day. And, what we still don’t know because, by all accounts, the storm was powerful, but it wasn’t as if it had an unusual confluence of factors that made it so different. It was a rather ordinary tornado with an extraordinarily consistent flow of energy. Not even an outsized portion of energy, just the right flow. Like a top that gets spun just right to stay remarkably stable, consistent, and true for a long time before wobbling and falling away.

I’m excited for the next steps in this process, which includes ever more revisions before a projected release date in time for the 100th anniversary of the storm in March 2025.